Response to NY Times article: Mammogram’s Role as Savior Is Tested

Tara Parker-Pope’s recent article in the New York Times Science Section discounts the role of mammography as an essential tool in the quest to save women from premature death due to breast cancer. She reports on the conclusion drawn by researchers Welch and Frankel from Dartmouth, who published a statistical analysis using epidemiologic data and computer software in this article in Archives of Internal Medicine this month. Their conclusion: “Most women with screen-detected breast cancer have not had their life saved by screening. They are instead either diagnosed early (with no effect on their mortality) or overdiagnosed.”

Tara Parker-Pope’s recent article in the New York Times Science Section discounts the role of mammography as an essential tool in the quest to save women from premature death due to breast cancer. She reports on the conclusion drawn by researchers Welch and Frankel from Dartmouth, who published a statistical analysis using epidemiologic data and computer software in this article in Archives of Internal Medicine this month. Their conclusion: “Most women with screen-detected breast cancer have not had their life saved by screening. They are instead either diagnosed early (with no effect on their mortality) or overdiagnosed.”

I strongly disagree with this conclusion, and with the suggestion that screening for breast cancer does not save significant numbers of women each year.

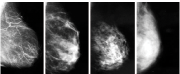

- Computer models and statistical analysis can be bent to create almost any desired outcome; stating that this constitutes “proof” is misleading. Common sense and our own experience, as well as numerous published studies using real patients, tell us that screening for breast cancer with mammography saves thousands of women each year. The earlier the cancer is found, the smaller it is, which means that it is less likely to have spread, greatly improving the odds of survival. Supplemental tests such as breast ultrasound and MRI, when used appropriately, can also help us find cancers at the earliest stage.

- Using the authors’ results, Parker-Pope estimates that in the U.S., somewhere between 4,000 and 18,000 women each year are saved by screening mammography. Although these numbers are likely lower than what is true, this is still a significant number of women who avoid premature death because they had their mammogram.

- There are some breast cancers found through screening that might not progress to the point of being life-threatening in the woman’s lifetime. The authors call this “overdiagnosis.” Until science can reliably tell us which cancers will progress and which won’t, and which don’t need to be treated, we will continue to treat the cancers we diagnose. How can they call this “overdiagnosis” and “overtreatment” when we don’t know which cancers will be the killers and which won’t?

- The analysis does not take into account the fact that finding breast cancer earlier through screening not only means a better chance of survival, but also means that treating the disease will be less time-consuming, less invasive, toxic, and painful, and less costly. The woman can potentially choose breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy instead of mastectomy), and is less likely to require chemotherapy, a miserable experience that affects the patient, her body, and her family for months if not years. The woman’s job standing can be affected as well. And for many women, taking a leave from work isn’t possible, as their job provides their health insurance coverage. If you’ve ever been through chemo or witnessed someone going through it, you’d probably choose to avoid it if you possibly could. In addition, if the cancer is found early, the woman won’t need to have all of the lymph nodes under her arm removed, and will avoid the potential complication of lymphedema (chronic arm swelling and pain). She can also avoid radiation treatments to the chest wall and axilla (underarm). Why are these issues not even mentioned in the Dartmouth analysis, or in Parker-Pope’s article? These considerations are extremely important for all women, and need to have a place in any conversation about the value of screening.

I practice at Montclair Breast Center, where we believe in taking a proactive approach to screening for breast cancer, tailoring our recommendations to each woman and her individual history, risk status, breast density, and personal concerns. As a result, our patients have significantly better outcomes than national averages. Breast cancer is the leading cause of death for women age 35 to 50, and the second leading cause of cancer death among women all ages, claiming 40,000 lives per year in the U.S. This is not a disease that we can be complacent about. Early detection is still our best line of first defense. Don’t let a “computer model” convince you otherwise.

Tags: Archives of Internal Medicine article on mammograms, breast cancer, breast cancer screening, Dartmouth mammogram study, early detection, mammogram, Montclair Breast Center, overdiagnosis of breast cancer, overtreatment of breast cancer, Tara Parker-Pope