Cathy Tatusko, Heroine of Breast Density Legislation in Virginia, Speaks Out

Cathy Tatusko, a breast cancer patient whose tumor was found at an advanced stage after years of “normal” mammograms, testified before the FDA last month in support of approval of a whole-breast automated ultrasound system. In her testimony, she tells her compelling and heart-wrenching story, and explains why she has been motivated to become a successful advocate for the cause of informing women about their breast density. She has graciously allowed me to post her testimony as a guest blog article.

Cathy Tatusko, a breast cancer patient whose tumor was found at an advanced stage after years of “normal” mammograms, testified before the FDA last month in support of approval of a whole-breast automated ultrasound system. In her testimony, she tells her compelling and heart-wrenching story, and explains why she has been motivated to become a successful advocate for the cause of informing women about their breast density. She has graciously allowed me to post her testimony as a guest blog article.

By Cathryn M. Tatusko

FDA Testimony (April 11, 2012)

Cathryn M. Tatusko

My name is Cathryn Tatusko. I am a breast cancer patient and an unpaid advocate. I live in Northern Virginia and neither required nor received any remuneration for my travel expenses to be able to testify before you today.

I am the woman who requested the breast density inform bill recently signed into law in Virginia. With substantial help from Are You Dense, I worked hard with other women and men to get our bill passed so that in the future Virginia women might be spared my fate. I am here today to speak in favor of the approval of the ABUS device for breast cancer screening as an adjunct to mammography in women with dense breasts. Thank you for the opportunity to tell you my story, and to explain what a difference this device would have made in my life only four short years ago.

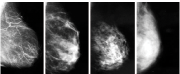

In September of 2009, I found a lump in one of my always-lumpy breasts that didn’t feel like the others. After a hellish week of medical tests and consultations, I received the devastating diagnosis of late-stage breast cancer. I was 54 years old at the time, and from the age of 40, I had not missed getting my annual mammogram. But only five months before I was diagnosed, a digital mammogram did not detect my large tumor.

I have a bachelor’s degrees in Journalism and Nursing, a certificate from an Institute of Slavic Studies, a Fulbright scholarship to Romania and a Master’s in Social Work. Many years ago, I even trained as an X-Ray Technician with the Army Reserves. In all but my first degree program, I finished at the top of my class. All of this is to say that I considered myself a fairly educated health consumer. But as the saying goes—we don’t know what we don’t know—and what I didn’t know is killing me.

Unlike many women I have since met or corresponded with who were diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer missed on mammograms, I had known for years that I had dense breast tissue. I had even been very aware of the little disclaimer on some of my mammogram reports indicating that dense breast tissue could make mammograms “less sensitive.” Tragically, what I didn’t know at the time, what I was never told by either my gynecologist or a radiologist—was the extent to which dense breast tissue could hide cancer on mammograms—masking up to 40% of tumors in women like me, with some estimates even higher. The other critical piece of information I did not know was that having dense breast tissue is itself a significant risk factor for developing breast cancer. Learning these things after being diagnosed left me feeling both beaten and outraged.

For two grueling years, I underwent very aggressive treatment, and for several months after finishing the initial treatments, my husband and I and all of our very extended family and friends cherished the hope that I had beaten the cancer. My hair grew back, I was feeling stronger, and I found the energy to push for the Breast Density Inform legislation in Virginia.

But on March 26th—just over three weeks ago and less than one month after Governor McDonnell signed our bill into law—my husband and I received even more devastating news than my initial diagnosis. My cancer had spread to my liver. In one shattering phone call from my oncologist after a CT scan, I learned that I had become a Stage IV cancer patient, with all hope of a cure stripped away.

I don’t know if any of you on the advisory panel or here representing the FDA has ever received a diagnosis of a life-threatening illness. If you have, perhaps you can identify with how difficult it is to go through what I’ve come to call “the telling,”—that is, the painful task of passing on to loved ones news I knew would break their hearts.

I am reading the new biography of Queen Elizabeth II, and I recently came across a quote that so perfectly captures what happens to all in one’s circle when such news hits. The line was simply this: “Grief is the price we pay for love.” I have lost so many dear friends to cancer—keeping vigil with each one of them—and I know very well the price of love that is being paid by all those who know and love me. The prayers and hopes they send in their cards and emails are sometimes overwhelming to me in the grief they convey, and I find myself needing to minister to them as they seek to minister to me.

I want to close by saying that for the life of me I cannot come up with one moral or ethical argument for withholding life-saving information or technology from any human being. I am only astonished that anyone could think differently. While I know my testimony will be dismissed by some of you as merely anecdotal, the science is there, and irrefutable. For the sake of my sanity, I have to believe that this hearing is somewhat pro forma, and that the ABUS device will of course be approved for breast cancer screening. To paraphrase an old folk song that I’m sure we all sang in our younger, more innocent days: “How many deaths will it take ’till we know that too many women have died?”

Thank you.

Tags: dense breast tissue, fda, late-stage breast cancer, Mammograms