First, Do No Harm: The Spectacular Failure of a Government Panel

As a veteran of World War II, my grandfather was a GI Bill success story, the first man to go to college from his impoverished neighborhood in Jersey City thanks to government at its finest. A card-carrying member of the state teachers’ union, and a politically active Democrat for most of his life, it came as something of a shock to me when, after a few decades of observing big government debacles, my grandfather became one of Ronald Reagan’s most ardent fans. I still remember his delight over the classic Reaganism, “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are, ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’” To paraphrase the Gipper, Here we go again.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a panel appointed during the George W. Bush Administration and supported by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, issued recommendations regarding breast cancer screening in 2009. This panel consisted of physicians in primary care (internists, pediatricians, Ob/Gyns), nurses, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and public policy officials. Not one single breast cancer expert (breast surgeon, oncologist, radiologist, radiation oncologist) was included at the table, and there was neither invitation nor opportunity for breast cancer experts to address the panel before the recommendations were handed down. The panel recommended screening mammograms every other year, beginning at age 50; this was a significant departure from the 2002 USPSTF recommendations, which called for annual screening commencing at age 40. Incredibly, the panel also recommended that women should not be taught or encouraged to do breast self-examination, and that physicians should not perform clinical breast exams on their patients to check for cancer. Instead of being applauded as one of the few interventions in the healthcare system that actually saves people, with a 30% reduction in breast cancer mortality in the U.S. since 1991, breast cancer screening was under attack.

To support its proclamations, the panel used a computer model to create new, non-peer-reviewed data extrapolated from previously published studies on mammography screening. (At least Colin Powell wasn’t tapped to bring in the poster boards this time. The man is still my hero, despite all of that.) Some of these papers were decades old. The USPSTF used the lowest estimate of mortality reduction attributed to mammography (15%) among the various numbers that exist in the literature (as high as 54%). Even with their selective use of a low mortality reduction figure to create their new numbers, the USPSTF’s own “data” confirmed that significantly more women would survive if mammography screening began at age 40. But they ignored their own data, and they claimed that the supposed “harms” of screening (discomfort, anxiety, being called back for additional pictures, potentially having a needle biopsy that turns out to be benign, the risk of diagnosing cancers that wouldn’t necessarily kill the woman— though no one can tell us which cancers those are at the current time) outweigh the benefit of lives being saved. This was clearly not an objective, impartial scientific judgment; this was a value judgment, made with the over-arching goal of creating cost-saving public-policy recommendations for a broken healthcare system.

In practice, we are beginning to see the fallout from that judgment. The infamous “death panels” have already landed, folks. But contrary to expectations, it’s not grandma’s plug that’s being pulled; it’s women in their 40’s who are being hung out to dry.

The yellow circle in the mammogram image below denotes a 0.7cm invasive ductal carcinoma in a woman in her 40’s who decided not to follow the USPSTF guidelines, and to continue annual screening. This patient’s cancer was detected at stage I, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 95%, an excellent prognosis. Her treatment consisted of a lumpectomy (breast conserving surgery) and radiation therapy. Chemotherapy was not required:

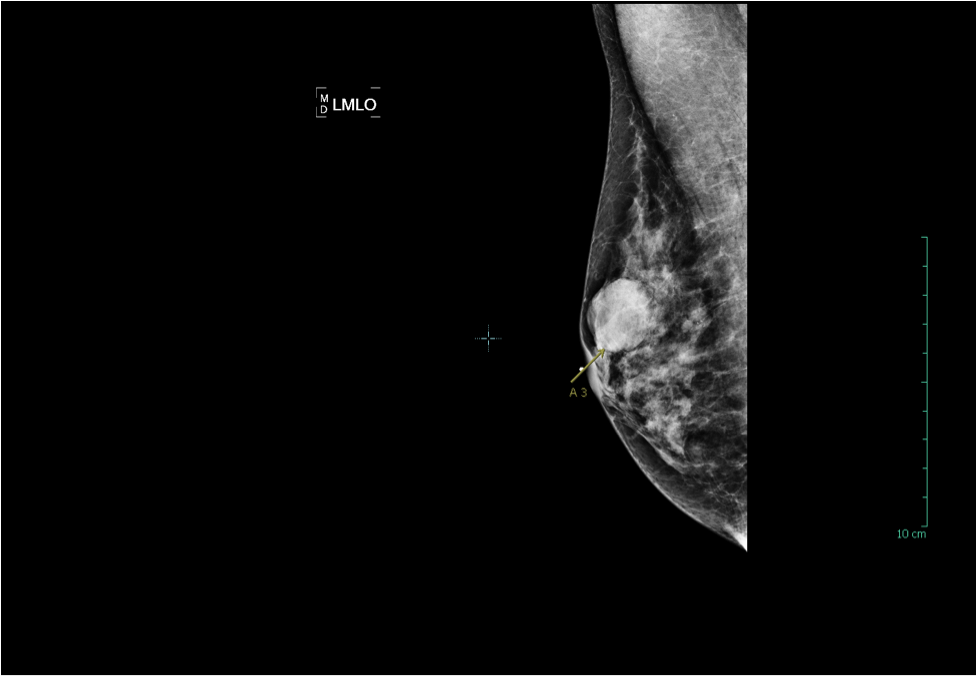

The mammogram image below is from a woman in her 40’s who had not yet had a baseline mammogram, and decided to put off screening until she turned 50 after she’d heard the USPSTF recommendations. One day she felt a lump in her breast, and her doctor sent her for a diagnostic mammogram. The yellow arrow in the image points to a 2.7cm invasive ductal carcinoma, at the site of her palpable lump. Unfortunately, this patient’s cancer had metastasized by the time it was diagnosed; her cancer is stage IV, with an estimated 5-year survival of 20%. Because her tumor is large compared to the size of her breast, a modified radical mastectomy (full breast removal) was recommended; the patient will also require many rounds of chemotherapy, and the best she can hope for is remission:

It has been estimated that if the USPSTF recommendations are followed as clinical guidelines, 20% of breast cancer deaths will occur in women who could have been saved. We have excellent data on mortality reduction as a result of screening women in their 40’s from numerous sources, including Dr. Laszlo Tabar’s group, Dr. Hendrick and Helvie’s study, and research presented from the Elizabeth Wende Breast Center in November 2011, to support the assertion that the USPSTF guidelines should be revised. In addition, this month’s edition of the journal Radiology published important original research concluding that mammography screening for 40- to 49-year-old women significantly decreases mortality.

The authors of this most recent study also found that cancers in women in their 40’s that were detected by mammograms required less invasive surgery (more lumpectomies rather than mastectomies; less lymph nodes removed), and these patients needed chemotherapy less frequently. These considerations were not even given a passing nod or mention by the USPSTF. These important additional benefits for women in their 40’s, when many people’s lives are impacted if these women become sick, include:

- Higher likelihood of being a candidate for breast-conserving surgery, with a better cosmetic outcome. Don’t let anyone shame you into thinking that you are shallow and vain if you believe this is an important consideration.

- Less likely need for chemotherapy—i.e. no hair loss, vomiting, fatigue, premature menopause, and a myriad of other side effects both temporary and permanent; less time missed from work and family obligations; less psychological trauma for yourself, your spouse and your children; less career disruption and the potential for discrimination due to your illness.

- Less expensive treatment. In a world where even patients with “good insurance” end up spending a great deal of their own money out-of-pocket when they have cancer, sometimes putting themselves and their families into debt to cover the costs, this consideration matters a great deal. Estimated cost to treat early stage breast cancer: $14,000. Estimated cost to treat advanced breast cancer: $140,000.

- Less likely need for complete removal of lymph nodes under the arm (axillary dissection), avoiding the potential lifelong misery of a chronically swollen and painful arm (lymphedema).

Any useful discussion regarding the value of screening for breast cancer must consider morbidity as well as mortality. It is severely unfair to women if these factors are left out of the debate, as they invariably have been until now.

I am not suggesting that screening mammography, even when started annually at age 40, is a panacea. If a woman has dense breast tissue, as half of women under 50 and 1/3 over 50 do, mammography is limited in sensitivity, many early cancers will not be seen on the mammogram, and a woman needs to discuss with her physician the possible need for an additional test in order to be effectively screened. Even for women who do not have dense breasts, mammography can be imperfect, which is why self-examination and clinical breast exam by your doctor are so important. In addition, women at high risk for breast cancer should develop an individualized, proactive screening plan with their doctor in order to protect themselves.

Breast cancer is the single most common cause of death in women age 35 to 50. If there’s any time to screen for it, it’s then. Don’t take one for the team on this. Cost savings for the system should not be attained by sacrificing women in our 40’s. An enlightened government should refrain from messing with what works, and should support efforts to make screening for breast cancer even more effective.

Tags: Axillary Disection, breast cancer screening, Invasive Ductal Carcinoma, Mammograms, Palpable Breast Lump, United States Preventive Services Task Force, USPSTF